H.K. v Australia (CAT, 2017)

Potential violations: CAT art 3

Unremedied

Unremedied

The UN says:

CAT (2017)[Australia] has an obligation, in accordance with article 3 of the Convention, to refrain from forcibly returning the complainant to Pakistan or to any other country where he runs a real risk of being expelled or returned to Pakistan.

Al Jazeera described the province of Balochistan as a 'bloody battleground', with more than 2,200 Balochi people having disappeared here between 2005-13. People targetted included rights advocates, political activists & armed fighters as well as "seemingly innocent men & women". (photo: Asad Hashim)

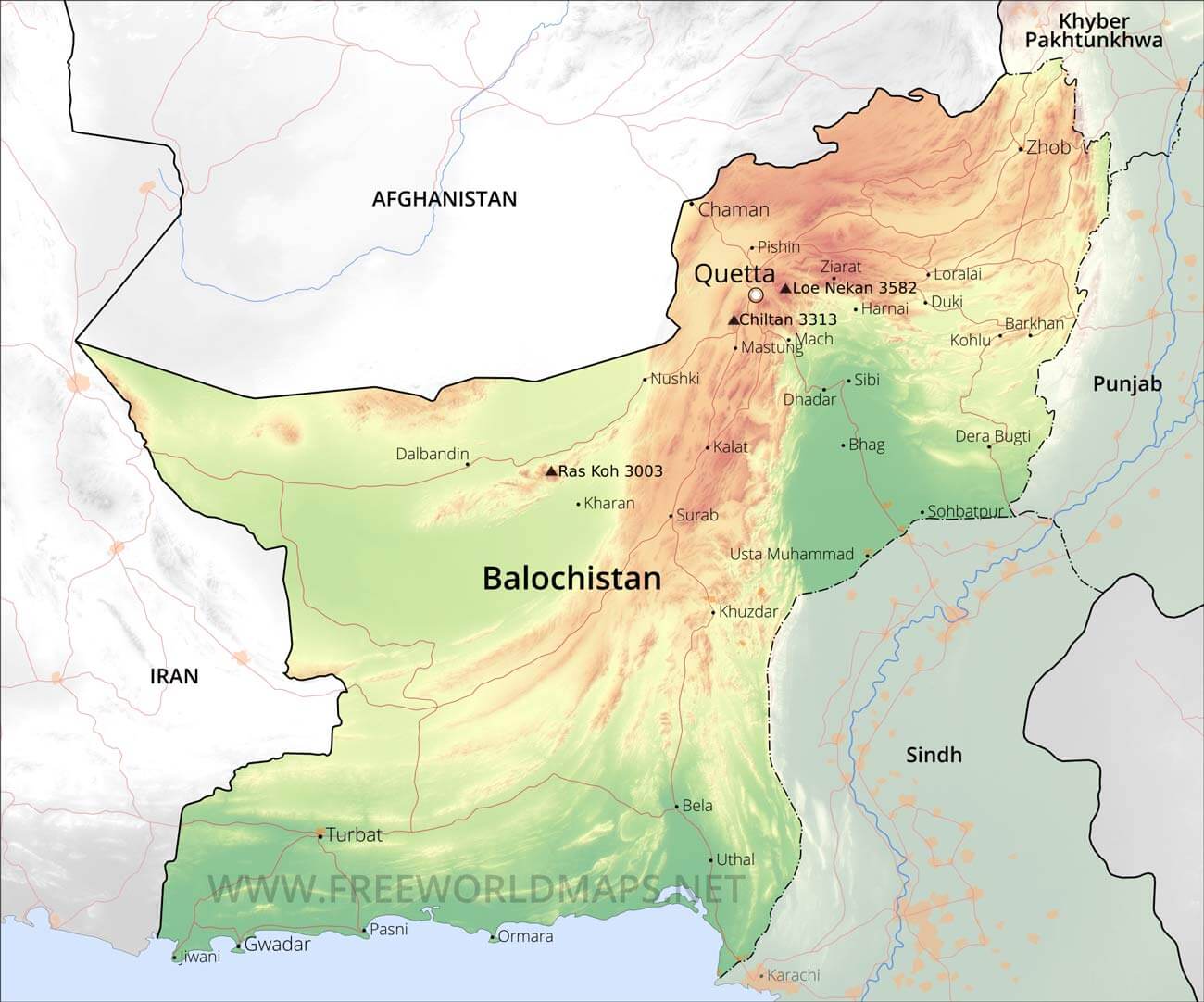

Mr H.K., a Pakistani national of Pashtu and Baloch heritage, was born in Quetta, capital of the Pakistani province of Balochistan. Baloch people are native to this province as well as to parts of neighbouring Iran and Afghanistan. Baloch nationalists seek greater freedom and autonomy; some are secessionists seeking a distinct, unified nation.

Mr H.K. spent most of his 20s working abroad and when he returned, Quetta was a site of fighting between government forces and Balochi nationalists. Mr H.K. was arrested by armed government authorities on suspicion of knowing about or cooperating with Baloch nationalists. They detained him for about 10 days, during which time he was interrogated, beaten and deprived of sleep. He was coerced with death threats into agreeing to act an informant and released. He attended a hospital for treatment. He was contacted and threatened further by his captors for over a month afterwards until he fled Pakistan.

Leaving his wife and 2 little children, he transited through Indonesia where he registered with UNHCR, then arrived on Christmas Island by boat in 2012 – an Australian territory 350km from Indonesia and about 1,550km from the Australian mainland – and applied for refugee protection. About 6 weeks later, his application was rejected. Immigration officials accepted that he had been detained and beaten, but not that he was of sufficient interest to be held for 10 days. It did not believe that he had been made an informant or that he was contacted by authorities after his release. It questioned his credibility due to inconsistencies over who he claimed had abducted and tortured him, and which groups he feared would persecuted him if he returned. Over 2013-15, Mr H.K. exhausted all avenues of appeal.

Mr H.K. petitioned the Committee Against Torture in September 2015. Shortly afterwards, the Committee issued interim measures asking Australia not to deport Mr H.K. while his communication was under consideration. Australia asked the Committee to lift the request and the Committee declined.

Mr H.K contended that Australia would breach Article 3 (prohibiting refoulement) if it deported him to Pakistan. Importantly, he pointed out that “absolute consistency can seldom be expected of victims of torture,” or indeed that interpreters can be expected to always use the same terms when rendering his story into English, but he insisted he had always been consistent in his refugee claim. As Australia did not contest his claim to have been arbitrarily detained and tortured by government authorities, its insistence that he should not fear returning to Pakistan is, he contended, “arbitrary and unreasonable” (para. 5.2).

The Committee agreed that Australia had not provided “any concrete arguments to justify” its refutation of some of Mr H.K.’s claims (para. 7.8). The Committee concluded that Mr H.K. had provided “sufficient evidence for it to consider that his return to his country of origin would put him at a real, present and personal risk of being subjected to torture” (para. 8) and that, as such, deporting him to Pakistan would violate article 3 of CAT. The Committee therefore asked Australia not to forcibly return Mr H.K. to Pakistan or to any other country where he ran a real risk of being returned to Pakistan (para. 10). It did not recommend any non-repetition measures, but sought a response from Australia within 90 days.

In its response, Australia criticised the Committee’s ‘approach’ and disagreed with its conclusions concerning Mr H.K.’s credibility and refoulement risk. Australia disputed the Committee’s ruling that deporting Mr H.K. would violate article 3 and informed the Committee that he would be “subject to Australia’s domestic migration processes” (para. 21).

Read the Australian government’s response to H.K. v Australia

Read the full decision: H.K. v Australia (May 2017)

Balochistan is the largest and poorest of Pakistan's 4 provinces, bordering Afghanistan to the north and Iran to the west (source: Freeworld maps)