Gnaneswaran v Australia (HRC, 2021)

Violations: ICCPR art 17, ICCPR art 23(1)

Unremedied

Unremedied

The UN says:

HRC (2021)Pursuant to article 2 (3)(a) of the Covenant, [Australia] is under an obligation to provide the author with an effective remedy. This requires it to make full reparation to individuals whose Covenant rights have been violated. Accordingly, [Australia] is obligated, inter alia, to proceed to a review of the author’s case taking into account [Australia’s] obligations under the Covenant and the Committee’s present Views, to arrange for the author’s return to Australia, if he so wishes, and to provide adequate compensation. [Australia] is also under an obligation to take steps to prevent similar violations in the future.

Mr Gnaneswaran holding his infant daughter. He was forcibly deported in the middle of the night in 2018 & has no way to ever see his wife and child again. (image: Tamil Refugee Council)

Thileepan Gnaneswaran, a Tamil Sri Lankan man, left Sri Lanka and was subsequently forced to flee Malaysia, arriving in Australia by boat in June 2012. He applied for refugee protection in November 2012. In January 2013, his protection visa application was refused. He appealed to the Refugee Review Tribunal which upheld the decision of the Immigration Department not to give him a protection visa. He subsequently applied for and was refused ministerial intervention on multiple occasions.

During this time, Mr Gnaneswaran lived in the community (not in detention) and in 2016, he got married.

In 2018, Mr Gnaneswaran was taken into Villawood immigration detention centre in Sydney. In July, his wife and 10-month-old Australian-born child were granted visas to remain in Australia. Two days later, Mr Gnaneswaran was advised he would be deported, with 3 days’ notice.

Mr Gnaneswaran petitioned the UN Human Rights Committee, claiming that deportation would violate article 7 (prohibition of torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment) as it would be dangerous for a Tamil with family links to the Tamil Tigers [LTTE] to enter Sri Lanka.

As the UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism wrote in 2017, at the conclusion of a country visit to Sri Lanka:

“Entire communities have been stigmatised and targeted for harassment and arbitrary arrest and detention, and any person suspected of association, however indirect, with the LTTE remains at immediate risk of detention and torture.”

Mr Gnaneswaran also claimed that his deportation would also violate article 17 (interference with family) read in conjunction with article 23(1) (family protection).

The day after receiving his communication, the Human Rights Committee requested interim measures, asking Australia not to deport Mr Gnaneswaran before a decision on his communication could be reached. However, it was too late: Australia deported him to Sri Lanka that same day. The Guardian said Australia acted "in defiance" of the interim order from the UN.

The Guardian reported that Mr Gnaneswaran was "forcibly removed from Australia in the middle of the night" (on 17 July 2018) and was "arrested and interrogated when he landed in Colombo, before being released from police custody" seemingly the next day (18 July). He was to face court the following week, according to The Guardian.

His separation from his wife and daughter will "almost certainly be permanent," wrote The Guardian. His wife Karthika Gnaneswaran’s visa "does not allow for family reunion, so she cannot sponsor her husband to return to Australia. And because of her 'well-founded fear of persecution' – recognised by the Australian government – she cannot return to Sri Lanka."

The UNHCR said at the time that Australia routinely separated families, often indefinitely and possibly permanently, through its asylum policies:

“This latest incident goes beyond a refusal to reunite families, to instead actively and indefinitely separate them. Current legislation prevents the Sri Lankan mother in this case from ever sponsoring her spouse to join her and their child in Australia. The husband and father is likewise prevented from ever obtaining even a short-term visa to visit his family. Sadly, the family members expect to be kept apart indefinitely.”

The UNHCR spokesperson said the family should be reunited.

The Human Rights Committee found Australia in breach of article 17 read in conjunction with article 23(1), amounting to arbitrary or unlawful interference with a family, given families are entitled to protection. Australia’s interference with Mr Gnaneswaran’s family life inflicted excessive hardship on him and his family, with no foreseeable prospect of reunification of the family. The Committee stated that this interference was disproportionate and unjustified by Australia’s objective to protect its borders.

Among the remedies recommended by the UN include Australia arranging for Thileepan Gnaneswaran’s return to Australia, if he so wishes.

Australia was asked to report back to the Committee within 180 days as to the measures taken in response to its views. This does not appear to have occurred.

Read the full decision: Gnaneswaran v Australia (October 2021)

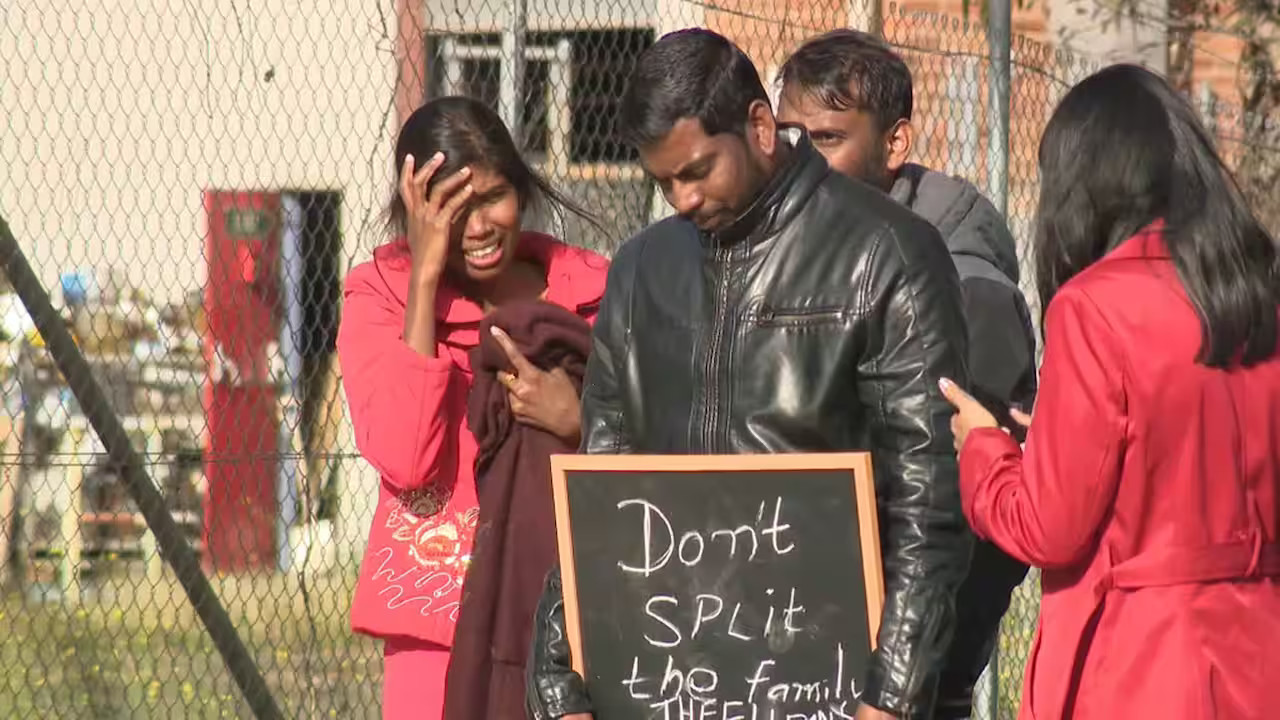

“We are all so depressed." Karthika Gnaneswaran (left), the author's wife since 2016. (image: SBS News)