Horvath v Australia (HRC, 2014)

Violations: ICCPR art 2(3)

Partially remedied

Partially remedied

The UN says:

HRC (2014)[Australia] is under an obligation to provide the author with an effective remedy, including adequate compensation. [Australia] is also under an obligation to take steps to prevent similar violations occurring in future. In this connection, [Australia] should review its legislation to ensure its conformity with the requirements of the Covenant.

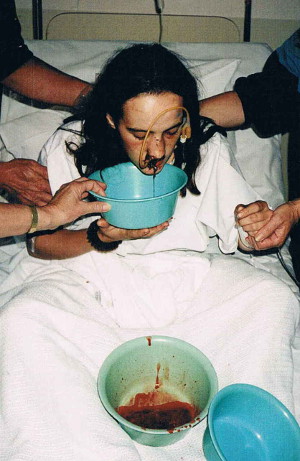

Corinna Horvath, on the night she was assaulted by police (photo by Corinna's mother)

In 1996, 21-year-old Corinna Horvath was assaulted by police during an unlawful raid on her Melbourne home. Her nose was broken and a tooth chipped. She was hospitalised for 5 days.

In 2001, Ms Horvath won a civil case at the County Court. After 40 days of evidence, the judge found police had committed trespass, assault, unlawful arrest and false imprisonment and awarded Ms Horvath $143,525 in compensation. This amount was reduced on appeal and Ms Horvath was denied leave to appeal to the High Court.

In Victoria, individual police officers, rather than the State, are liable to pay damages for unlawful conduct. Where a police officer is unable to pay, the victim can go uncompensated. Further, none of the police involved has been disciplined or prosecuted by the State. Ms Horvath seeks adequate compensation and effective discipline of the police officers involved.

In 2014, the UN Human Rights Committee found that Ms Horvath's right to an effective remedy was violated, in relation to the cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, arbitrary arrest and detention to which she was subjected, and the interference with her home and privacy. The Committee recommended legislative reform in Victoria and adequate compensation for Ms Horvath.

2014 update: Partial remedy in record time!

On 19 September 2014, Corinna Horvath obtained an individual remedy some 5 months after the UN found her rights had been violated and that she should be compensated. Ms Horvath received a written apology from the Victorian Police Commissioner and an ex gratia payment as compensation for the violent assault on her by police in 1996.

In October, Victoria's corruption watchdog, the Independent Broad-based Anti-Corruption Commission (IBAC, founded in 2011), engaged retired judge Bernard Teague to review how Victoria Police had handled the Horvath case.

Congratulations to Ms Horvath and her legal team. Thank you to everyone who campaigned for her right to an effective remedy.

2015 update: Criminal charges recommended against leading police officer

In October 2015, Justice Teague recommended to IBAC that Victoria Police should investigate bringing criminal charges against Leading Senior Constable David Jenkin, who is still a serving police officer. Possible charges range from assault to intentionally causing serious injury.

2016 update: Further remedy, courtesy of the anti-corruption commission

In November 2016, IBAC charged Leading Senior Constable David Jenkin with recklessly causing injury, recklessly causing serious injury, intentionally causing injury and intentionally causing serious injury. Jenkin, still a police officer, was removed from operational duties, with a Magistrates' Court hearing scheduled for 19 December.

The Age newspaper reported that Ms Horvath no longer feels let down by the justice system, but remains 'troubled by how long the investigation had taken' (over 20 years).

Non-repetition obligations relating to the Horvath case remain unaddressed

Despite the exceptional progress outlined above (compared with most Australian individual communications), the Horvath case has not been fully remedied.

In its 2014 decision, the UN Human Rights Committee found that Australia "is also under an obligation to take steps to prevent similar violations occurring in future" by means of law reform "to ensure its conformity with the requirements of the Covenant."

Ms Horvath's lawyers remain concerned about "significant and systemic issues [of] integrity, transparency and independence" that were overlooked or inadequately addressed by the IBAC report in 2016. Flemington Kensington Community Legal Centre identifies persistent and unaddressed problems with the current police complaints system as including "inherent bias, low substantiation rates of meritorious complaints, complainants being ‘locked out’ of the complaints process, and lack of public trust and confidence in the complaints process as a whole."

Internal police investigations fail the test of independence, yet IBAC is not sufficiently independent or transparent either. Complaints against police, including allegations of serious misconduct, "are routinely investigated internally by line managers within Victoria Police, which does not reflect public interests or international human rights standards. Further, IBAC processes are not transparent to the public or complainants." Read more.

2017 update: Parliament investigates police oversight

In 2017-18, the Victorian parliament is conducting an inquiry into the external oversight of police corruption and misconduct. Remedy Australia made a submission to the parliamentary committee with the following recommendations: To fully remedy the HRC's views in Horvath, we urge the Victorian Government and parliament to:

- Implement an independent investigatory system that aligns with international human rights standards and ensures all victims of human rights abuses arising from police misconduct receive an effective remedy.

- Implement an independent system for police oversight that aligns with international human rights standards and ensures police officers in breach of human rights are disciplined.

- Introduce compulsory, evidence-based human rights training for commencing and in-service police officers in Victoria.

- Amend the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) to expressly include the right to an effective and enforceable remedy of any person whose rights are violated, notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity.

- Amend the Victoria Police Act 2013 (Vic) to ensure the State is liable for all police misconduct.

Read more about our recommendations here. The IBAC Committee is due to report its findings in June 2018.

David Jenkin's committal hearing was deferred and is now listed for January 2018.

2018 update: Police officer faces trial

In November 2018, Leading Senior Constable David Jenkin was tried in the County Court of Victoria for intentionally causing serious injury, recklessly causing serious injury, intentionally causing injury and recklessly causing injury.

The jury acquitted Jenkin and Ms Horvath said she considered the case over.

Verity Smith of the Flemington Kensington Community Legal Centre said Victoria still needs "a fully independent, fully resourced body able to look into matters of this serious nature" when police officers are accused of criminal or corrupt offences.

Act on the Horvath case now:

Sign this super-quick letter to the federal Attorney-General and the Premier of Victoria.

Background

The events in question:

Corinna Horvath and her partner, Craig Love, had friends David and Colleen and their two boys over for a barbecue one Saturday afternoon in 1996. At about 9:40pm, two police officers knocked on the door wanting to inspect her unroadworthy car for evidence it had recently been driven, contrary to police instruction. Ms Horvath refused and asked them to leave. A scuffle ensued, in which the police claim they were assaulted by Horvath and Love, but a County Court judge found that Horvath and Love had 'used no more force than was necessary' to prevent the police trespassing on their property. The police left and called for reinforcements.

At 10:30pm, 5 police cars arrived and 8 policemen got out and surrounded the house. One of the police ‘yelled … in a loud and aggressive voice’ that the occupants should open the door, as they intended to make an arrest. The occupants refused, asking for evidence of a warrant. The officer replied that they did not need one. One of the officers then kicked open the front door ‘with great and sudden force’, striking Ms Horvath's friend David in the face with the door, causing injury and constituting an assault.

This same officer then entered the house, ‘pursued David … brought him to the floor and, in the course of so doing, struck him on the right side of the head and hit him at least once with a baton across his lower back.’ Another police officer then informed the first that David was not the man they sought to arrest.

The first officer then entered the lounge room where he tackled Ms Horvath to the floor, then 'brutally and unnecessarily' punched her in the face up to a dozen times, thereby 'rendering her senseless'. Ms Horvath has no recollection of this assault. She suffered a broken nose and chipped tooth, bruising and scratches to her face and body. Two officers then handcuffed her 'in a manner that restricted her from reducing the pain and blood flow from her nose or otherwise relieving her injuries' and dragged her to their divvy van. Meanwhile, her friend Colleen was forced to the floor and held there with a knee in her back. Ms Horvath and Mr Love were both arrested and taken away by police.

Ms Horvath was 'not provided with immediate medical treatment' in police custody, but was instead 'left screaming in pain in [a] cell'. She was 'eventually discovered by a police doctor who contacted her parents', who called an ambulance. She was released from custody at about 12:20am and taken to hospital for emergency treatment.

A week later, Ms Horvath returned to hospital and was admitted for 5 days, requiring surgery to repair her facial injuries. She is left with scars on her nose and has been treated for anxiety and depression arising from the assault.

Read the full decision: Horvath v Australia (March 2014)

Ms Horvath, admitted to hospital a week after the assault (photo by her mum)