Elmi v Australia (CAT, 1999)

Violations: CAT art 3

Unremedied

Unremedied

The UN says:

CAT (1999)The Committee considers that substantial grounds exist for believing that the author would be in danger of being subjected to torture if returned to Somalia.

… in the prevailing circumstances, the State party has an obligation … to refrain from forcibly returning the author to Somalia or to any other country where he runs a risk of being expelled or returned to Somalia.

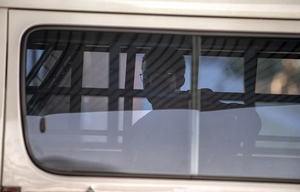

Perth airport, 1998: Sadiq Elmi crossing the tarmac in a security van in Australia’s second attempt to deport him to Somalia, in defiance of CAT’s interim request. The deportation was disrupted by civil society action and abandoned. (photo: Ross Swanborough)

A Somali asylum seeker from a persecuted ethnic minority resisted refoulement because he feared torture by the Hawiye clan dominant in his home town of Mogadishu. Somalia was a ‘failed state’ engulfed in civil war, the Communist dictatorship having collapsed. Sadiq Elmi’s refugee claim was rejected by Australia and he petitioned the Committee Against Torture to prevent his deportation. CAT found that, in the absence of a conventional government, the Hawiye clan was exercising quasi-governmental control, at least in the capital, and the threat of torture by this clan could, under these circumstances, fall under the Convention (article 1). Therefore, Australia would violate article 3 if it deported Mr Elmi to Somalia.

Australia responded, not by issuing him with a refugee visa, but by allowing Elmi to re-apply for asylum from the beginning, keeping him in detention throughout. His second application for asylum also failed and, in January 2001, after more than three years in detention, Elmi ‘chose’ to leave Australia, ‘heading in the general direction of Somalia.’ His destination and present whereabouts are unknown.

Given Mr Elmi appeared to leave Australia voluntarily, and reportedly withdrew his communication, CAT has considered the case closed.

Remedy Australia, however, questions the voluntariness of Mr Elmi’s departure from Australia. A voluntary departure cannot be refoulement, but only if truly voluntary. The ‘principle of voluntariness … follows directly from the principle of non-refoulement,’ says the UNHRC and, as such, ‘is the cornerstone of international protection.’ The UNHCR’s Handbook on Voluntary Repatriation deems that in situations where people are ‘subjected to pressures and restrictions and confined to closed camps, they may choose to return, but this is not an act of free will.’ Where people are ‘being subjected to arbitrary detention or severely restrictive detention regimes,’ Amnesty International, likewise, has ‘serious concerns about whether returns can be truly voluntary.’ ‘Failed’ asylum seekers subject to mandatory detention in Australia have very little choice. Mr Elmi’s choices appeared to be to end his prolonged detention by agreeing to leave, or else endure indefinite detention until forced deportation.

Remedy Australia considers Australia did not act in good faith in the matter of Elmi v Australia. The Committee Against Torture advised Australia that ‘substantial grounds exist for believing that [Mr Elmi] would be in danger of being subjected to torture if returned to Somalia.’ Beyond his eligibility for complementary protection under the Torture Convention, the implication of CAT’s decision in Elmi was that Mr Elmi also had a valid claim under the terms of the Refugee Convention: one which CAT deemed to be a well-founded fear of persecution on the basis of his ethnicity. Yet Australia did not appear to take account of this view, nor the sources on which it was based, in reviewing Mr Elmi’s refugee claim. Australia rejected his second refugee claim in spite of this finding.

While Mr Elmi’s fate is unknown, given that the State Party arranged for his departure from Australia, it must know, and ought to make public, his destination when he boarded that flight in January 2001, to permit an assessment of whether Mr Elmi was returned ‘to Somalia or to any other country where he [ran] a risk of being expelled or returned to Somalia.’ Until this information is made available, Australia’s compliance with CAT’s Final Views in Elmi v Australia remain in doubt.

Read the full decision: Elmi v Australia (May 1999)

For source details, see Remedy Australia's 2014 Follow-up Report (PDF 1.3Mb).